It’s Dark-eyed Junco season! According to Cornell Lab of Ornithology, this “snowbird” is one of the most common and familiar North American passerines. They usually show up in Shasta County in November and grow in number until they disappear in March, except for higher elevations like Lassen Volcanic National Park. We spotted a pair of juncos with a juvenile at Manzanita Lake in July last year during our annual campout!

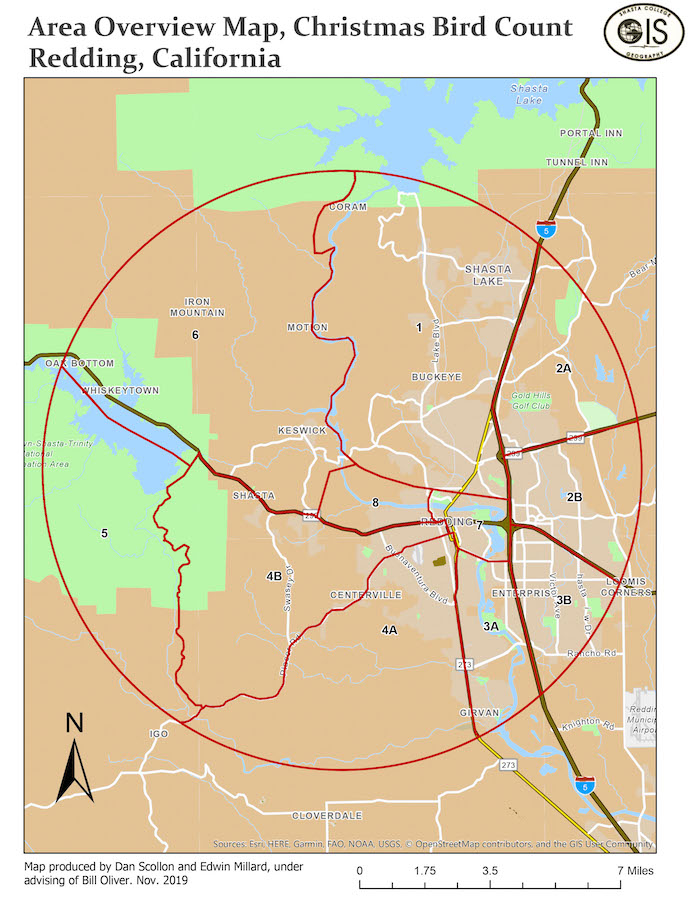

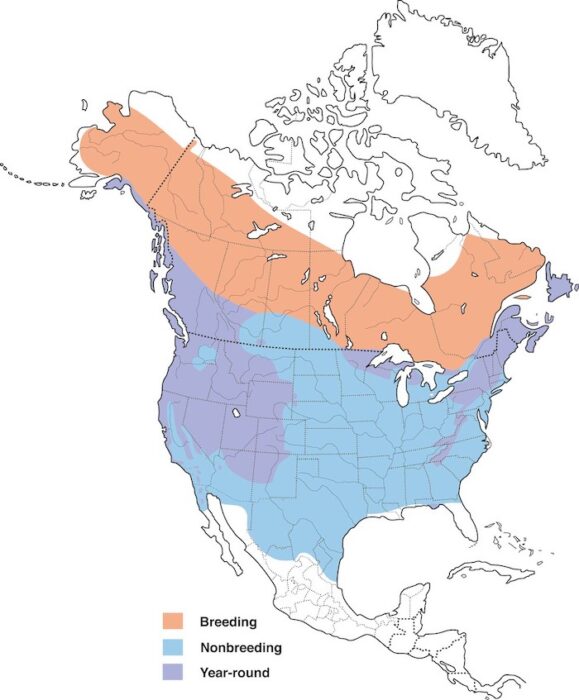

As you can see from this map, the Dark-eyed Junco appears throughout the United States and Canada, and even spills over into northern Mexico. A large number breed in the far North but many reside year-round in the western United States.

One way to identify the Dark-eyed Junco from a distance, even if they are flying around, is their conspicuous white outer tail feathers. These photos are from Miles and Teresa Tuffli who run the bird blog “I’m Birding Right Now“. They graciously gave me permission to use their DEJU tail feather photos.

Even this juvenile Dark-eyed Junco already has white outer tail feathers!

There are five recognized sub-species of Dark-eyed Juncos, Slate-colored, Oregon, Gray-headed, White-winged, and Guadalupe. The most common here in Shasta County is the “Oregon” subspecies, followed by the Slate-colored Dark-eyed Junco. This is a typical Oregon Junco similar to the photo at the top of the post but most likely a female.

And a different image of a female Oregon Dark-eyed Junco.

Here are a few images of the more rare (in our area) Slate-colored Dark-eyed Junco…

and another.

We love these Dark-eyed Juncos that visit us every winter. Keep an eye out for those rarer sub-species. You never know when you might find a rare Junco in our midst!