Lazuli Bunting Male

This season last year we had a torrent of reports of lazuli buntings scouring through the Whiskeytown brush and in the chaparral all around the North State. These little birds attract attention because they are visually stunning.

Western Bluebird Male

A superficial description of a male lazuli bunting makes it sound like a western bluebird: blue on the head and topside, pale belly, and a rusty-colored breast. But there’s no room for confusion in daylight viewing. The bluebird is darker, almost cobalt, its breast a burnt brick. The lazuli bunting, in contrast, looks like plugged-in high wattage gemstones–turquoise lapis up top, a moonstone belly, and red jasper on the breast. The bird doesn’t actually glow in the dark, but it has that look to it.

Lazuli Bunting Male

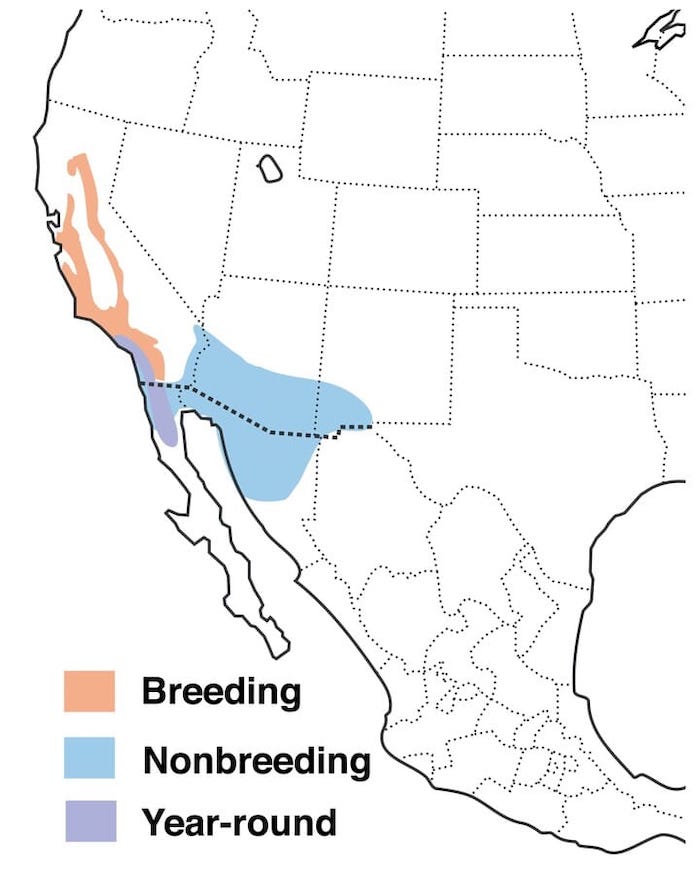

Each spring the females, with the same feather pattern as their mates but browner over all, follow up from Mexico a few days behind the males, who arrive first on the breeding grounds–Great Basin oases or brushy thickets throughout the West. The females will build their nests low to the ground, but first the males establish nesting territories by chasing and singing other males away.

Lazuli Bunting Female

Their music is vital. Buntings are like most songbirds in the way males stake out their breeding grounds by singing. But the song means so much more, too.

Yearling males arrive on breeding grounds with no song of their own. But like young people developing their place, they assimilate snippets from their older kith and kin, and piece those musical fragments into a pattern that becomes their own. In this way, they develop distinctive individual songs that share the phrasing of their community. The neighborhood recognizes and tolerates some encroachment from birds that share their song. Other buntings with unfamiliar music are vigorously chased off.

In evolutionary terms, buntings’ vocal cues serve to support perpetuation of a localized gene pool, a condition that can develop both distinctive beauties and destructive in-breeding. But change, for better and worse, is written into the laws of nature.

The tropics, so rich in the conditions for abundant life, churn out an amazing variety of species. It seems that buntings of yore expanded northward from South America, likely sometime well after our continents joined perhaps fifteen million years ago. But the birds became separated east and west when they hit the Great Plains, the vast grassland of North America that sported bison but not the brushy thickets where buntings make their homes. Divided, the western birds developed into what we call lazuli buntings, and the eastern group became indigo buntings.

Indigo Bunting Male By Kenneth Cole Schneider

More recently, however, the Plains have been breached; agriculture and other development introduced brushland where buntings from both east and west could live; and both could sing there, and hear each other’s songs. Apparently the young of both species readily adopt songs from either. They become musically bilingual, and then, as often happens when the same language is spoken, the two groups begin to court and nest together. Their young are proving to be fertile, so the hybridizing and rejoining of the two bunting species is ongoing in mid-America.

Whether that reunion will reach the west coast, and what new beauties it may produce, remains to be seen. Conditions change, and so then do nature’s children.

Lazuli Bunting Male

For now, though, we can enjoy the treat of our time. Lazuli buntings are striking compatriots. You might not recognize the nuances of their warbler-like trill as well as they do, but look for their blazing color in our North State brushlands!